- FR

- EN

For many people, the first time they would have heard of Messenger Ribonucleic Acid (mRNA) was during the COVID-19 pandemic when it was the topic of many media articles. Famously, it was mRNA technology that delivered the first COVID-19 vaccine to be approved by the medical authorities, and went on to protect millions of lives from the severe effects of COVID-19, across the world.

However, the background of using mRNA vaccines started well before the pandemic and was used in developing treatments for cancer. With COVID-19 no longer posing the same level of threat, mRNA vaccine developments are now focusing their attention back to cancer.

Indeed, the husband-and-wife team of Profs. Ugur Sahin and Ozlem Tureci, who developed the mRNA Pfizer BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, had previously worked together in the field of cancer immunotherapy for many years and were amongst the first researchers to recognise the potential of mRNA vaccines for the treatment of cancer.

Recent developments have seen mRNA cancer vaccines being evaluated in combination with drugs that enhance the body’s immune response to tumours, with some very exciting results.

mRNA-based cancer vaccines have been tested in small trials for nearly a decade, with some investigators believing the success of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines could help accelerate clinical research on mRNA vaccines to treat cancer.

Currently, there are many clinical trials testing mRNA treatment vaccines in people with various types of cancer that have shown promising results, including pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, ovarian cancer and melanoma.

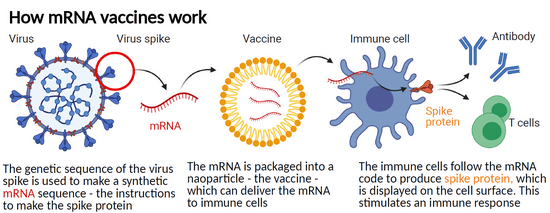

Unlike traditional vaccines which introduce a weakened or inactive form of a virus or bacteria into the body, mRNA vaccines work by introducing a small piece of genetic material into cells, which then instructs them to produce a specific protein. Once in the body, the mRNA instructs cells that take up the vaccine to produce proteins that may stimulate an immune response against these same proteins, when they are present in intact viruses, or tumour cells.

To explain this further, using the example of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that was responsible for causing the COVID-19 pandemic, the mRNA included in the Pfizer-BioNTech and the Moderna vaccines instructs cells to produce a version of the “spike” protein that protrude from the surface of the virus. The immune system is then able to identify the spike protein as foreign and mobilises some immune cells to produce antibodies and other immune cells to fight off the apparent infection. Having been exposed to the spike protein free of the virus, the immune system is then primed to react to a subsequent infection with the actual SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Unlike vaccines used to prevent infectious diseases, cancer vaccines are used in the treatment of those who have already developed a cancer, to prevent it from spreading or recurring. mRNA vaccines for cancer typically use an individual’s own cancer cells to produce the mRNA, which is then injected back into the patient to stimulate an immune response against the cancer.

This approach is known as “personalised cancer immunotherapy”, and it has the potential to be highly effective because the vaccine is specifically tailored to a person’s own unique cancer cells. By doing so, the risk of rejection from the immune system or other adverse effects such as the damage to healthy cells and tissues, is minimised.

Another key advantage of cancer mRNA vaccines, is that they have the potential to stimulate a broad immune response against the cancer, which could lead to long-term protection against recurrence. Traditional cancer treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy can kill cancer cells. However, they do not necessarily prevent the cancer from coming back in the future. In contrast, cancer mRNA vaccines may be able to train the immune system to recognise and destroy any remaining cancer cells, which could help prevent the cancer from returning.

Results of the first demonstration of efficacy for an investigational mRNA cancer treatment in a randomised clinical trial were released in December 2022 by a spokesman for the pharmaceutical and biotechnology company, Moderna.

The statement from Moderna explained the results of the phase 2 clinical trial, in which 157 people with advanced stage melanoma underwent a surgical resection of their tumour. From there, individuals were either given the mRNA vaccine as well as an immunotherapy treatment involving the drug Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) or just the immunotherapy treatment alone. Researchers said those who had both the mRNA vaccine as well as immunotherapy had a 44% reduction in cancer recurrence, when compared with the group who only had immunotherapy.

More trials will be required, but the finding is very significant and shows huge potential.

The UK government recently announced that it will partner with BioNTech to fast-track up to 10,000 patients into clinical trials of mRNA immunotherapies to treat cancer. The alliance builds on lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic, during which vaccine development accelerated because the country’s National Health Service (NHS), academia, the regulator and the private sector worked together, according to a BioNTech press release.

The project, dubbed the Cancer Vaccine Launch Pad, will be run by the NHS and Genomics England and hopes to take advantage of the clinical trial, genomics and centralised healthcare data infrastructure, afforded by the NHS. Patient recruitment will start in September 2023.

The technology is extremely expensive, as it’s personalised, particularly when added to the cost of immunotherapies that may also form part of the overall treatments. However, BioNTech suggests it is affordable for healthcare systems, and the involvement of the NHS will allow the funding for this valuable research to continue at a faster pace than would otherwise be possible.

The trials of yet undisclosed mRNA cancer immunotherapies in adjuvant or metastatic settings will run until 2030. Around one-third of BioNTech’s wholly owned mRNA vaccine candidates are already in UK trials, all using a fixed combination of mRNA-encoded tumour-associated antigens. These include BNT111 for advanced melanoma, BNT112 for prostate cancer and BNT113 for head and neck and other cancers.

We asked SCOR Oncology CMO, Professor James Brenton for his view on these developments, and he advised the following:

These are very exciting results as they show that immunisation with the BNT111 RNA vaccine against melanoma cancer cells induces prolonged responses in patients who had not responded to standard immunotherapy. Because of the importance of these findings, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation for BNT111 which means BNT111 will progress faster to wider clinical use. In the UK, we will soon see RNA vaccines used in new clinical trials via the Cancer Vaccine Launchpad partnership.

The last decade has brought major improvements in survival for some cancers because of immunotherapy. Bespoke RNA vaccines offer technological advances that now offer more benefits for patients. Exciting times!

Cancer is an important condition for underwriting and over the years there has been some improvement in terms for specific types of cancer. Indeed, recently SCOR’s underwriting manual SOLEM has revised significantly underwriting guidelines with reduced ratings for cancers including those of the breast and testicles. Updated colon cancer guidelines will also be released shortly.

Many of the improved ratings have been possible where there has been early detection and is related to treatment improvements. However, with further advancements in cancer treatments such as immunotherapy, personalised medicine and improved diagnostics, the underwriting of cancer is going to be different in the future, particularly with regards to advanced cancers that reach stage 3 and 4, that are often currently uninsurable.

It is also quite likely that in time, completely new guidelines for advanced cancers will be developed that will be unlike traditional cancer ratings which typically are shaped with high monetary extras decreasing over time. Instead, we are likely to be using flat extras or extra mortality ratings, that would be more reflective of the risk, where the early years following cancer will be improved, with an increasing risk as time goes on.

From a claim’s perspective, obvious changes with improving cancer prognosis will potentially be fewer death claims. The impact on terminal illness claims could also be significant, with increasing life expectancy for claimants with advanced cancer. There could be more claims issues connected with the current criteria of 12 months life expectancy. This is likely to add further fuel to the debate as to whether the current design of terminal illness benefit needs to be changed.

Additionally, disability claims related to income protection and total and permanent disability could be affected as together with increased survival, there is also the prospect of better quality of life. As the treatment removes the need for chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgery, patients would need less recovery time and may be able to continue working.

In summary, although it is still early days, the potential for these vaccines is huge and the early results are promising.

Profs. Ugur Sahin and Ozlem Tureci feel that the first cancer vaccines could be available before the end of the decade and with the NHS partnership, it may not be too long before we are seeing examples of this amazing development included in the medical evidence obatained at both underwriting and claims stage.