- FR

- EN

In November 2022, the pharmaceutical company Eisai released the full results from its phase 3 clinical trials of a new Alzheimer’s treatment drug called “lecanemab”. This is the first drug that has acted to successfully slow down the destruction of the brain in Alzheimer's by tackling the condition itself, rather than the symptoms it creates. This is achieved by reducing accumulations of an abnormal protein in the brain called amyloid.

Currently, people with Alzheimer's are given other drugs to help manage their symptoms, but none until now have been able to change the course of the condition. Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that these results have been heralded as “momentous” by Alzheimer’s Research UK and many dementia researchers, who see this as a breakthrough moment, ending decades of failed attempts to find an effective treatment for the cause of the condition and showing that a new era of drugs to treat Alzheimer's disease, is possible.

To put this development into perspective, lecanemab has already been approved for use in the US (from January 2023) and should it become approved by the regulators in the UK, it would be the first new Alzheimer’s drug to be approved for almost 20 years.

Dementia is not a disease, it is a clinical syndrome affecting loss of higher mental function and, typically, two or more cognitive domains, such as episodic memory (new memories), language function or decision making (executive function), spatial awareness (visual spatial function) or movement execution (apraxia).

Dementia has become common with an aging population. In the UK, it affects 900,000 people and is a leading cause of death. In the UK alone, it is estimated that 1.6 million people will be affected by dementia by 2050. However, age is not the only risk factor and when diagnosed under the age of 65, individuals are referred to as having ‘young’ or ‘early onset’ dementia. Worryingly, the disease process could potentially start in patients as young as 30, even though they appear asymptomatic.

There are many causes of dementia, with Alzheimer's disease being the most common, accounting for about two-thirds of cases at older ages and 35% of patients under the age of 65. Other causes are related to conditions such as vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies.

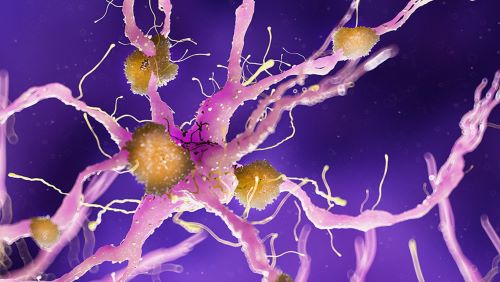

The human brain contains tens of billions of specialised cells called neurones that process and transmit information via electrical and chemical signals. These neurones send messages between different parts of the brain, and from the brain to the muscles and organs of the body. What happens with people who have Alzheimer’s disease is that this communication among neurones is disrupted, resulting in loss of function and cellular death.

One of the features of Alzheimer’s disease, often seen in MRI scanning of the brain, are “amyloid plaques” These plaques form when a naturally occurring protein in a brain cell or neurone, called amyloid precursor protein (APP), is not broken down properly. This results in a new protein being produced called beta amyloid

Where APP would have been naturally recycled, beta amyloid cannot be recycled and starts to build up outside the neurone, sticking to other remnant beta amyloid proteins and creating a plaque. Beta amyloid plaques are thought to be one of the reasons behind cognitive decline as they compromise neurotransmission because the plaques build up between the neurones. However, this is not the only character trait associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Beta amyloid plaques are often associated with the presence of neurofibril tangles. Unlike plaques, neurofibril tangles are observed inside the neurone and result from abnormal accumulations of a protein called tau. In healthy neurones, tau normally binds to, and stabilises, microtubules. However, in Alzheimer’s disease, abnormal chemical changes cause tau to detach from microtubules and instead they stick to other tau molecules, forming threads that eventually join to form tangles inside neurones. These tangles block the neurone’s transport system, which harms the synaptic communication between neurones.

As neurones are injured and die throughout the brain, connections between neural networks may break down, and many brain regions begin to shrink. By the final stages of Alzheimer’s, this process—called brain atrophy—is widespread, causing significant loss of brain volume.

Lecanemab is a disease modifying immunotherapy drug. It works with the body’s immune system to clear amyloid protein build up from the brains of people living with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease.

More specifically, lecanemab is an antibody treatment. Antibodies already exist in the human body – they are a type of protein produced by the body’s immune system to fight against the disease.

Lecanemab is given to patients intravenously and works by targeting amyloid protein in the brain ‘triggering’ the brain’s immune system to clear it out.

The appeal of a new drug that directly targets the removal of beta amyloid plaques would see a move away from current Alzheimer’s treatments, which only manage a patient's symptoms, by increasing their levels of acetylcholine (a neurotransmitter that aims to increase communication (neurotransmission) between neurones). These drugs have never been seen as a cure or effective in slowing the disease progression and is why a medication aimed at the removal of beta amyloid is such a huge breakthrough.

Eisai released information on lecanemab’s stage 3 trial, called Clarity-AD, that involved 1,795 people with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease who have amyloid accumulation in their brains. The trial showed that the drug slowed down loss of memory and thinking skills in 27% of people taking the drug, against those taking a placebo.

Researchers estimate that over 18 months, the drug may slow the progression of Alzheimer’s by approximately 7 months. The research team also found that the drug slowed down the decline in quality of life by up to 56%.

Trials for lecenemab will continue to understand the longer-term effects of taking the drug, and whilst there is already approval for its use in the US, it is likely to take a little more time before lecenemab is approved for use in the UK, with a likely release date being at some time in 2024.

Although these results only show some limited success, the importance of the findings cannot be underestimated as it has proven the theory that amyloid accumulation is responsible for Alzheimer’s beyond doubt and will open new avenues of research guided by this initial success.

In the anti-amyloid approach to Alzheimer’s, other drugs have shown promise and there are over 100 amyloid targeting drugs currently going through clinical trials.

Because not all types of dementia have the same mechanisms for causing damage to the brain, lecenemab will not be so effective for these other types of dementia.

Dr Dennis Chan has been a CMO for SCOR for several years and is a University Lecturer and Honorary Consultant Neurologist, with a particular interest in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease prior to the onset of dementia. His comments relating to this news were as follows:

"Clearly, it’s promising that this is the first drug to show some cognitive benefits, but caution is warranted because the effect was small, there were significant side effects which include brain haemorrhages, and the cost will be very high, many £10,000s per annum per patient. It also has to be given intravenously and the NHS does not have the infrastructure to deliver this at present."

We do not yet know who will benefit most, but it is highly likely to be those with pre-dementia Alzheimer’s disease. We also have no knowledge yet of the optimal age range as this was not looked at in the trial.

Nonetheless, I welcome it as the potential first of a new generation of drugs and also because it highlights the need to alter clinical practice to improve early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease is not a common cause of claim for any of the protection products. i.e. life, critical illness or income protection. This is largely because it is a condition that is more commonly seen in older ages, where protection cover is less commonly purchased. However, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease are commonly included in critical illness cover, where it can provide invaluable cover, particularly if it affects someone younger in life, as can happen.

The Association of British Insurers (ABI) recently updated the model wording for Alzheimer’s disease in the latest Minimum Standards for Critical Illness document, so that it includes all types of dementia, with severity criteria as follows:

Dementia including Alzheimer’s disease – of specified severity

A definite diagnosis of Dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, [before age x] by a Consultant Geriatrician, Neurologist, Neuropsychologist or Psychiatrist supported by evidence including neuropsychometric testing.

There must be permanent cognitive dysfunction with progressive deterioration in the ability to do all of the following:

As explained in our December 2022 SCORacle edition, changes were made to the recommended ABI wording, by bringing together all forms of dementia in one definition. The revised wording also provides greater clarity with regards to the required severity criteria for claims. These changes included:

With the potential that drugs such as lecenemab will become more successful in slowing progressive disease, together with improved diagnostic techniques also being developed, the new ABI wording should serve well to ensure there is sufficient “futureproofing” of the definition. This is important to ensure the claims criteria are positioned at an appropriate severity level and to protect against claims for milder or non-progressive types of dementia, that in turn provides consistency and premium stability for the future.

Hopefully, the early breakthrough of this new drug will result in research developing more treatments that will be even more effective in tackling this devastating disease, not only extending life, but also helping those affected have a better quality of life.

With the aging population and the growing numbers of people that will be living with dementia, it is likely to become an even greater issue for our health systems and breakthroughs of this nature will help in this regard.

SCOR will of course continue to monitor these developments and keep you updated of any further important news.